high arctic people and change

In recent decades, the opening of the Arctic has not only renewed transatlantic endeavours, but also raised significant environmental concern. As the Arctic icescape continues to respond dramatically to contemporary climatic changes, discussions surrounding the region have necessarily examined the human and wildlife implications of environmental sensitivity. Climate change is, undoubtedly, a pressing matter in the long-term and large scale but is it the only Arctic matter that deserves our attention? Driven by this thought, I travelled to Qaanaaq, Greenland in 2017 (Figure 1) to learn from the local people about coping with 21st-century Arctic change.

Fig. 1: Map of Greenland. Qaanaaq, north Greenland is the study site.

Qaanaaq is an “Inughuit” (northern Greenlandic) town that is one of the world’s northernmost human settlements. Its roughly 650 inhabitants are descendants of the semi-nomadic Thule Inuit, who migrated from Alaska and founded the village of Thule over two millennia ago. Thule remained a hub of the far north when Greenland became a Danish colony in the 1720s until it was, ultimately, vacated in 1953 and replaced by a U.S. airbase during the Cold War. The building of this Thule Air Base necessitated the relocation of roughly 200 Inughuit, the majority of whom were displaced 100 kilometres north to what would become Qaanaaq. 1953, thus, marked a significant turning moment for the Inughuit of Thule that also became the starting point for my research. I wanted to examine the specific changes that accompanied the displacement and how they might have impacted the Inughuit of Qaanaaq as the community encounters changes in the 21st-century.

After speaking with seven of Qaanaaq’s Inughuit residents, I identified three outstanding processes the local people were exposed to and significantly impacted by:

1) Modernisation

2) Tensions and Stagnancy

3) Contemporary Climate Change

Using this “triple exposure” framework, I ultimately learned that contemporary climate change is, indeed, not the most pressing concern for all Arctic communities. Rather, at least for the Inughuit of Qaanaaq, contemporary climate change has only amplified deeper-rooted sociocultural concerns that began with modernisation in 1953.

Exposure #1: Modernisation

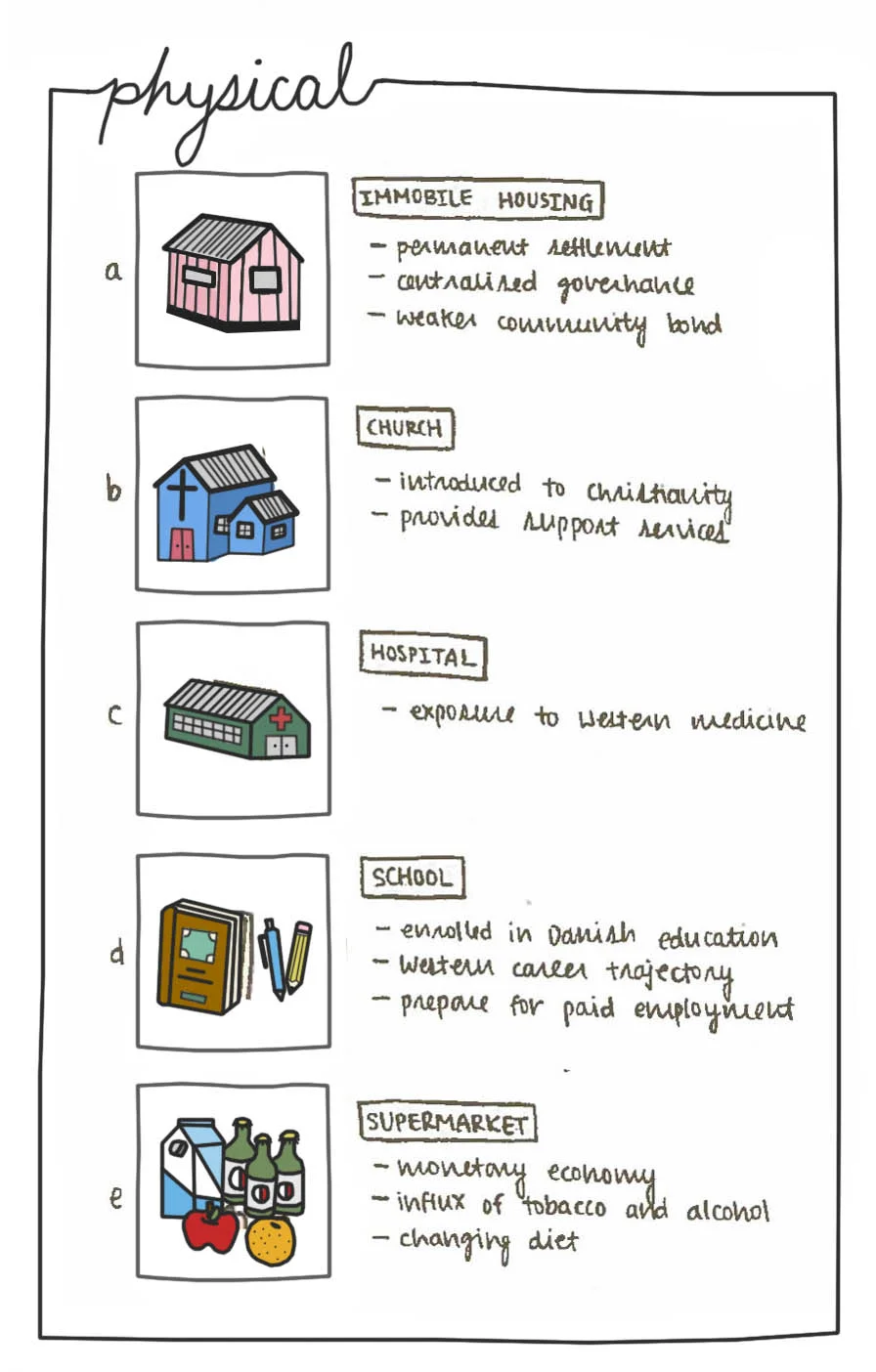

Learning from their ancestors and encountering for themselves Greenland’s climatic extremes, the Inughuit have developed a fierce resilience to the inevitable environmental challenges of Arctic life. Come 1953, however, the Inughuit were exposed to a kind of change that was unprecedented. Qaanaaq is essentially a Danish town built for the Inughuit and in the span of three decades, the Inughuit experienced rapid modernisation that began with physical change (Figure 2). Immobile housing, a Catholic church, hospital, school, and supermarket were among the establishments erected in Qaanaaq that were at once foreign yet fundamental to life in Qaanaaq. Having led traditionally semi-nomadic lives, the Inughuit now conformed to a lifestyle founded on Western values, becoming exposed to sedentariness, centralised governance, Western faith, medicine, and diet, Danish education, monetary economy, and drinking culture.

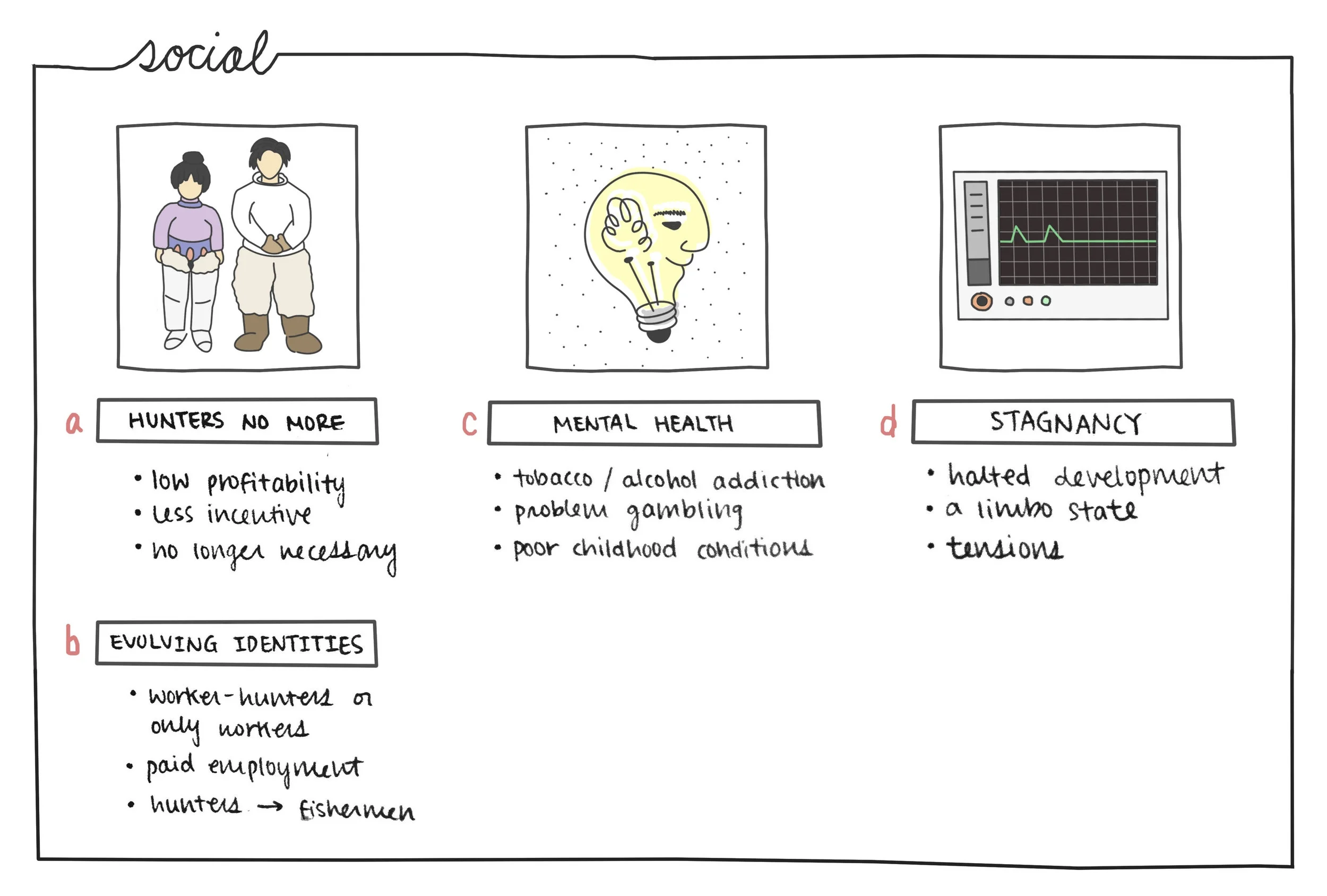

As the Inughuit modernised and adapted, they also experienced sociocultural change (Figure 3). These changes have had lasting effects on the Qaanaaq community into the 21st-century, sparking uncertainty over cultural and traditional identity and creating new social health concerns. For one, the Inughuit have recognised a significant decline in hunting as the traditional means of sustenance. As requirements for survival in Qaanaaq shift from placing food on the table to securing income to buy food and pay bills, hunting has become less necessary and less rewarding since the arrival of imported goods and especially after the 2010 EU ban on seal products. Today, it seems paid employment is the new form of breadwinning and the household, historically cared for by a hunter and his wife, has evolved into a dynamic characteristic of modern metropolis–that of either two paid employees or, in the very least, a hunter and a paid employee. In addition to evolving identity, modernisation has placed pressure on the Qaanaaq community’s social health. Though not conclusively causal, there is a strong correlation between the timing of modernisation and a noticeable increase in addiction, abuse, gambling, and mental illness in Qaanaaq and Greenland overall. In times of great change and great stress, people cope differently; while some in Qaanaaq found comfort in worship and counselling, others sought substances and gambling. The number of individuals struggling with addiction in Qaanaaq may be relatively slim but the consequences are far-reaching in such a compact community. Particularly for children, alcoholism, abuse, and neglect in the household have disrupted familial relations and schooling, enabled under-age drinking and smoking, and negatively affected mental wellbeing.

Fig. 2: Physical changes associated with the establishment of Qaanaaq in 1953. The Inughuit a) began to lead sedentary lifestyles in immobile houses, b) adopted the Christian faith, c) became dependent on Western medicine, d) children grew up with the Danish education system, and e) the introduction of a permanent monetary economy meant paid employment became the basis of survival.

Fig. 3: Sociocultural changes that lagged behind and underlay physical changes associated with the founding of Qaanaaq. For one, a) the traditional Inughuit identity as hunters is no longer sustainable and b) this image has and continues to evolve. Such fundamental changes have also been associated with c) community concerns over addiction, abuse, and mental wellbeing. Finally, d) Qaanaaq has been experiencing localised stagnancy that has become a source of frustration and tension for the last few decades.

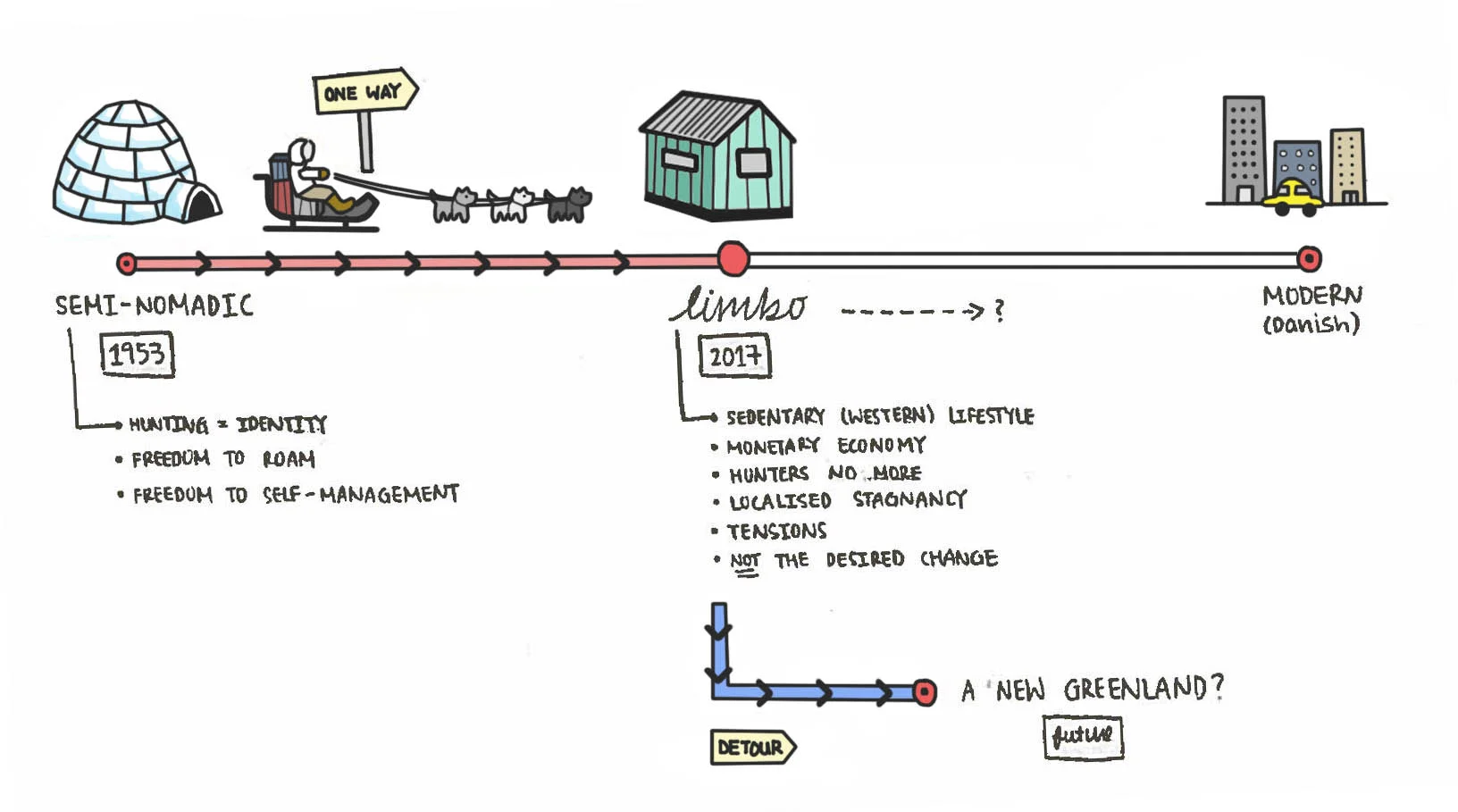

The first three decades after Qaanaaq’s establishment in 1953 were, thus, characterised by rapid modernisation based on Danish and Western ideals. As the Inughuit adapted and coped with the unprecedented changes prompted by modernisation, they then encountered a second exposure. Contrary to the first 30 years, the most recent decades in Qaanaaq have been marked by stagnancy, tension, and a general backwards progression from the lifestyle achieved with modernisation.

Exposure #2: Stagnancy and Tensions

Of my findings, this was the most unexpected. Before visiting Qaanaaq, I familiarised myself with Greenland’s history, though the literature I read somewhat skewed my understanding. The papers largely examined developments in Nuuk, Ilulissat, and other major colonial settlements that have since transformed into large cities and I, thus, assumed modernisation was uniform throughout Greenland until I was told otherwise. The Inughuit I interviewed explained that modernisation had not merely ceased as rapidly as it began, but developments have actually followed a backwards trajectory over the last three decades. As the standard of living established after modernisation lowers, underlying tensions between Qaanaaq and external entities become apparent with each unproductive change (Figures 3 and 4).

The first and ongoing tension to materialise is that between Qaanaaq and the Greenlandic government. Tensions developed with the 1953 Thule displacement but changes in recent years have aggravated matters. After a nationwide municipal reform in 2008, Qaanaaq lost its status as a municipal capital and government resources were redirected towards the new municipal capital of Ilulissat (Figure 1). Consequently, the local hospital in Qaanaaq no longer accommodates long-term patients or emergency cases; schoolteacher turnover rates increased; political representation decreased; mental health counsellors make fewer annual visits; and municipal regulations generally favour Ilulissat. Notably, the Inughuit have become more aware of both their geographic distance from the rest of Greenland and their political separation. Especially at a time when Greenland is making strides towards independence from Denmark, Qaanaaq’s diminished representation and say in political affairs have caused the community to feel voiceless. With matters related to hunting, the Inughuit have felt a similar kind of neglect, as municipal hunting seasons have not addressed climatic differences and the lag in the onset of optimal hunting conditions, between Ilulissat and Qaanaaq. As such, Qaanaaq hunters have generally been granted shorter hunting seasons, which are further limited by quotas that do not reflect the needs of the community.

Fig. 4: The “Modernisation Spectrum”. A simple visualisation of the sociocultural transformations the Inughuit have experienced since Qaanaaq was established. My research suggests that, presently, Qaanaaq exists in a kind of limbo state due to decades of stagnancy.

Aside from disagreements with the government, the Inughuit have faced opposition from the WWF, Greenpeace, and other international organisations over hunting practices. From the Inughuit’s perspective, these outside entities have not fully understood the philosophy behind hunting – to hunt sustainably, live considerably, and prioritise need over want – that also embodies the essence of Inughuit life. Having always observed this mind-set, Qaanaaq hunters do not believe their practices have jeopardised ecosystems as suggested by international organisations. Ultimately, to the Inughuit, they are forgotten people and their inability to achieve desirable change, and growing indifference from this powerlessness, have heightened frustrations as Qaanaaq encounters 21st-century climatic changes in its stagnant state.

Exposure #3: Contemporary Climate Change

Recalling my initial pondering about the magnitude of climate change on Arctic people, I think it has become clear that, at least for the Inughuit of Qaanaaq, sociocultural concerns have been most pressing. Despite this, contemporary climatic changes have certainly not gone unnoticed. In fact, the Inughuit have observed especially unusual environmental variations in recent years related to the onset, duration, and extent of sea ice. The later annual onset of sea ice has coincided with the arrival of Danish supply ships that, even during my stay, has been significantly delayed due to impenetrable sea ice during historically-accessible times. Warmer oceans have, furthermore, shortened the duration and extent of sea ice, limiting hunters’ movement and access to wildlife and contributing to shortened hunting seasons, but incidentally attracting more marine life to Qaanaaq. Climate change has certainly created advantages and disadvantages, though observed challenges have mainly aggravated existing sociocultural concerns and are not the root of the Inughuit’s difficulties. Should municipal hunting regulations better reflect Qaanaaq’s climate and hunting needs and should Qaanaaq gain greater access to resources, perhaps contemporary climate changes would place less pressure on the community.

Conclusion

In Qaanaaq, rapid modernisation and sudden stagnancy over the course of 60 odd years have produced transformative consequences that 21st-century climate change now intensifies. Yet, despite facing this triple exposure, the Inughuit are here to stay. As one of Qaanaaq’s residents said to me, “you need to be tough to live here.” The Inughuit have certainly demonstrated great resilience in the face of changes unprecedented in both nature and in magnitude. The history, culture, and identity of Arctic people extend beyond their hunting heritage. For the residents of Qaanaaq, climate change is one concern among many unresolved and underlying sociocultural concerns.